I first visited the islands of Sanibel and Captiva, off Florida’s Gulf Coast, six years ago. I basked under the sun on its powdery white sand beaches and catered to my cravings with locally caught grouper sandwiches and every permutation of the ubiquitous key lime imaginable—from pies to margaritas to pancakes.

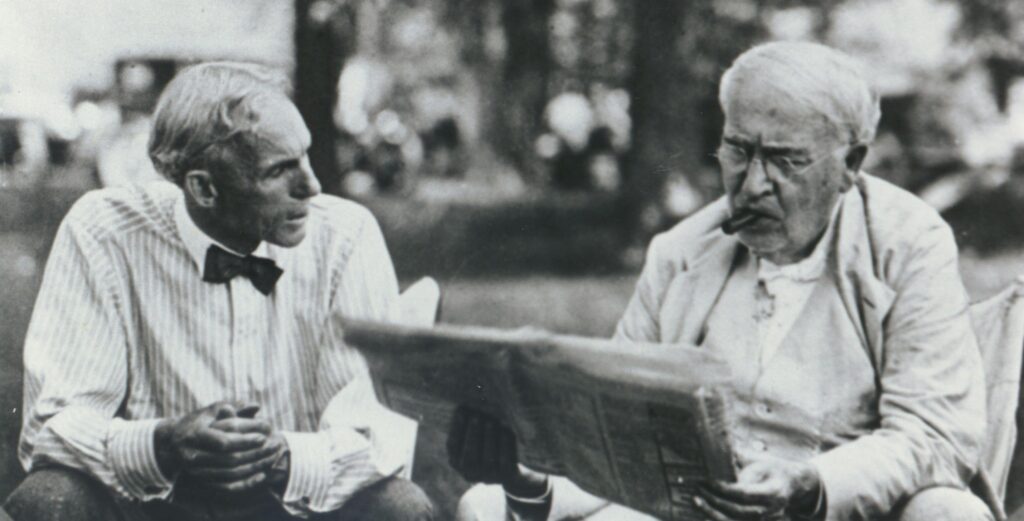

My recent return visit to Sanibel was motivated by my curiosity related to how historic figures such as Henry Ford and Thomas Edison found their way here, and why? It turns out Ford and Edison were relative newcomers to a region with a history spanning close to 6,000 years.

The start of Sanibel

Historians believe Sanibel was formed by sand and sediment pushed by centuries of ocean storms to form a land mass over 12 miles long and three miles across at its widest point. Three thousand years later, documents show tribes of up to 50,000 Calusa Indians (“fierce people”) as the island’s first residents who, in fact, controlled most of southwest Florida.

Millions of shells comprise the beaches of Sanibel; collecting them is a prime tourist activity today. But during the days of the Calusa, the larger shells, conch and whelk in particular, were utilized as utensils for eating, spears for fishing, and to form burial sites of which the mounds still exist as historical proof.

Fast forward to 1513, when explorer Juan Ponce de León searched for the elusive Fountain of Youth and happened upon Sanibel. He christened it Santa Isybella in homage to Queen Isabella, and for seven years, he fought to gain control of Calusa land for the glory of Spain. The Calusa were large, well-built warriors who fought back hard. One of their arrows hit Ponce de León and forced him to retreat to the island of Cuba, where he subsequently died.

Victory by default

The Spanish, however, continued their attempts to take control of Sanibel. In an ironic twist, the European diseases they brought with them to Florida—from tuberculosis to measles—caused the demise of the Calusas within 200 years.

Referred to as “The Buccaneer Coast” in the early 1800s, legend has it that the notorious José Gaspar, a.k.a. Gasparilla, the pirate (possibly fictitious), buried stolen treasure from hundreds of ships he plundered from his base on Sanibel. It is also said his crew abducted the females from those ships and held them captive to serve as concubines or be held for ransom on the portion of the island that later became Isle de los Captivas, the precursor to Captiva Island.

Post-Civil War, the U.S. government secured Sanibel as a lighthouse reservation. The 98-foot iron Point Ybel Light can be visited today, as can a schoolhouse built in 1892 to educate the children in the settlement that grew around the lighthouse.

In 1928, docks were built on Sanibel and regular ferry service allowed visitors and vehicles to be shuttled to the island from the mainland until 1963, when the Sanibel Causeway became an option for automobiles to make the trip fast and easily.

Retreat for notables

Severe hurricanes in 1921 and 1926 split the island in two (the smaller part became Captiva), and the saltwater soaking of the land put a halt to the agricultural crops of grapefruit, watermelon, and vegetables. However, these two beautiful islands quickly found a new, modern way to make a living: the hospitality industry.

Wealthy industrialists from up north, including inventor Thomas Edison and automotive genius Henry Ford, spent winters in Fort Myers, Florida, and often hopped the ferry to Sanibel for rest and relaxation at a resort known as The Sisters (in 2021, it’s called Casa Ybel Resort).

Following the footsteps of Ford and Edison, other American innovators were drawn to the island. Clarence Chadwick spearheaded an agricultural project on the Isle de Los Captivas, today’s Captiva, planting a 330-acre key lime plantation. That site is now the South Seas Resort.

Eventually, the island was democratized, and anyone desiring to live on Sanibel could order a home-in-a-box from a catalog, get it delivered by ferry from the mainland, and assemble it on the island. Some of these manufactured homes are still standing today, but most have been relocated away from hurricane zones.

My second visit

It’s an effortless drive across the 2-lane, 3-mile Sanibel Causeway from Fort Myers to Sanibel and Captiva islands. Sanibel parts ways with Captiva at a fork in the road. From there you’ll drive along, able to spot some of the distinctive flora known to thrive in this hot, humid region: begonias, milkweed, coneflower, canna lily, sea grape, and salt myrtle. Bookending the blacktop is the same sugary sand found on the island’s beaches. Watch for signs warning of gopher and tortoise crossings.

Sanibel feels more like an exotic Caribbean island than a part of Florida, especially at beachfront resorts like Sundial, Casa Ybel, and Sanibel Moorings, all with optional villas and suites for short- or long-term rentals. I stayed at Sanibel Moorings in a suite shaded by jackfruit trees; its hanging, ripe fruits were the size of footballs. A long, narrow wooden pier projects from the back edge of the resort to the Gulf of Mexico, skimming over the tops of protected sand dunes and their grassy vegetation.

Channeling Messrs. Ford and Edison, who once made this place the hottest destination in town, my travel companion and I took a seat at a corner table at Thistle Lodge, located at Casa Ybel Resort. It boasts a bi-level outdoor deck for dining and is the nearest to the ocean of any restaurant on the island. Indoors is a chic bar and galley dining area with a wall of windows from which to enjoy sunsets.

While children frolicked in the nearby pool, I sipped on a very adult red wine from Paso Robles, California, and nibbled on a warm baguette smeared with honey butter.

Caesar salads here are crisp, refreshing plates of perfection, topped with near-translucent slivers of anchovy. The filet mignon is rubbed with a proprietary spice blend created by Omar, the Jamaican-bred chef who’s incorporated the flavors of his homeland into many dishes on the Thistle Lodge menu.

Edison would have lit up had he been served Omar’s spicy octopus appetizer. And had Ford tasted the filet mignon topped with scallops and its “special” turmeric-based sauce, he’d have been geared up to return to Thistle Lodge again and again for yet another historic and fascinating experience on the island of Sanibel.