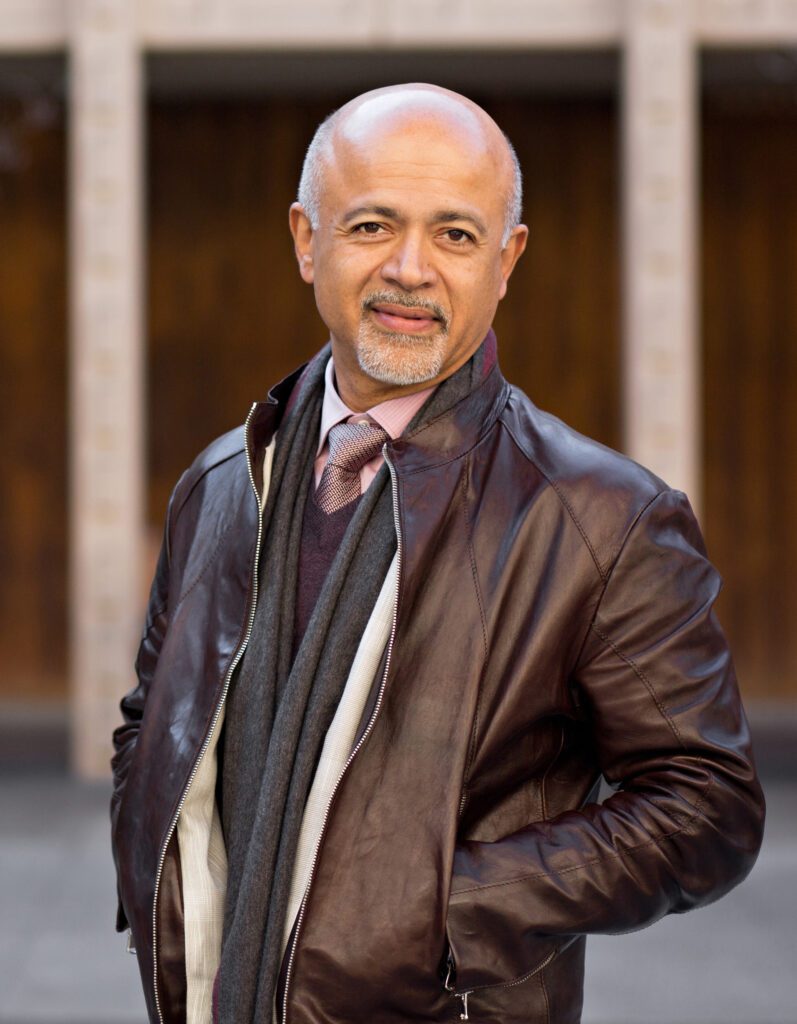

With a list of accolades as long as some novels, it’s hard to fathom where Abraham Verghese finds the time to write bestselling books. For one, his titles include MD, MACP, professor, and Linda R. Meier and Joan F. Lane Provostial Professor, and vice chair for the theory and practice of medicine at the School of Medicine at Stanford University. He is a physician known for his gentle bedside manner and care.

With the introduction of technology, many physicians need to remember the gracious act of focusing on the patient versus relying on the data without engaging the patient. The noble calling of medicine is massive commitment on its own, without the writing which brought him into the spotlight, particularly his epic novel, Cutting for Stone. He received the Heinz Award in 2014 and was awarded the National Humanities Medal by President Barack Obama in 2015.

I had to know how this brilliant man straddles today’s data-driven, scientific world of medicine and the ambiguous creativity of writing with such ease. Verghese shares, “Well, that’s funny, you know. I don’t think of them as two separate professions. I know that sounds disingenuous, but the writing comes from my stance on medicine. Medicine is deeply meaningful, and it’s from that place that I begin to have the impulse to write.”

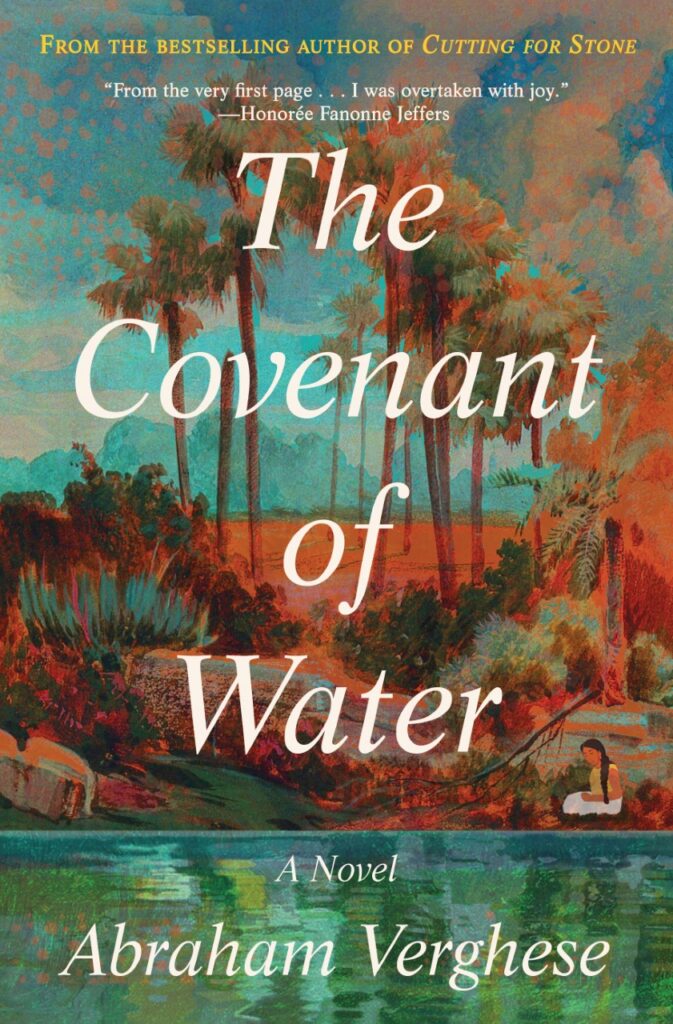

It took Verghese 10 years to write Covenant of Water, and he shares why, “This one took almost a decade, partly because it was just a long process. I’m not one of these writers who knows the whole story before they start. I know some of the story, and then I start writing, and then things reveal themselves, but, unfortunately, they often reveal themselves in the wrong direction for six months. Then I find out and, hundreds of pages later, I return to something else.”

“I often say that I write in order to understand what I’m thinking.”

–Abraham

“The muse of the right brain begins to speak, and it is mysterious. I had a unique experience recently. I’m recording the audiobook of my latest book, The Covenant of Water, and while doing this, I’ve begun to see connections in the book that I swear I hadn’t planned. And, you know, so it’s like your subconscious is just putting things in there that you didn’t even know. It’s mysterious.”

Verghese’s writing spoke to me on such a visceral level that I wanted to know if he practiced any faith. He shared a story about a recent church visit: “In Fremont, there is the same Saint Thomas Christian community church that I was raised in, and the service was in the Syriac language. And I had goosebumps, I tell you, because it was just all my childhood ritual. Even though I didn’t understand it; my parents didn’t. But they’re memories, and my mother had just passed away. So, it was very powerful. So, you asked me if I’m spiritual, well, faith is the absence of proof.”

I wanted to know what he learned about himself when writing,

and his answer was profound.

“Every book, especially my first two nonfiction books, I thought I was writing about something I observed, whether HIV in Tennessee or the phenomenon of doctors and drug addiction. But, inevitably, I became a character in the book. Because you’ve got to turn the camera on people so intensely in a nonfiction book, when the camera wants to swing towards you, you can’t shut the reader out. You know, writing a memoir was interesting, but also painful. I was ’fessing up to things that I didn’t feel all that comfortable ’fessing up to you, but I’m not standing up on Oprah and jumping on the couch and confessing things. The reader has to do me the honor of reading my book to learn this stuff about me. With fiction, it’s much more subtle in that you’re picking a subject without you knowing why you’re picking them. Some recurring themes occur in both my fiction novels, one being abandonment. I feel like I didn’t do justice to my older two boys, and I’m still atoning for it.”

Verghese has written another novel which Oprah has proclaimed as, “One of the best books I’ve read in my entire life,” The Covenant of Water. We spoke about his experience writing that novel during a pandemic. Verghese explains, “I was writing it during COVID, but I was writing about the era between 1900 and 1970 in Kerala where there was a lot of pain, suffering, and illness. The book is very medical, and it just seemed to me striking how in illness and suffering, whether we live in the 21st century or back then, we reach for the same thing. We’re looking for meaning; we’re looking for faith to sustain us. And then, when we find it, when we find redemption of some sort; we know, even if it’s inadequate, we find it from the same things. We find it in our relationships, faith, and human connections. So, I’m learning all the time about humanity, about medicine, about writing, about forgiveness, and myself.”

What’s so ironic is that books inspired Verghese to become a physician. He shared his journey with me: “For me, the novels that led me to medicine were The Citadel and Of Human Bondage.”

Decades and continents later, Verghese found himself in the HIV era because of this training in infectious diseases. He was practicing medicine in the small town of Johnson City, Tennessee, where everyone said he would see one HIV patient every other year because it was an urban condition. But in a short time in that small town of 50,000, that one patient every other year increased to about 100 patients a year.

Verghese continues, “It’s crazy how quickly it became apparent that this was a tremendous American story of migration. It was a story of young men leaving their homes for jobs and education, but also because they were gay. They didn’t want to live their lives under the scrutiny of their families. So, they spent decades in the big city. Often their partners got sick first and died, and now they were coming home because they were ill. And so, there I was at the tail end of this migration. I wrote a scientific paper describing this. But even as I read the paper, it felt like the language of science didn’t capture the heartache of those families. It didn’t capture the nature of the voyage. It didn’t capture my grief. I was also getting burned out by the intensity of HIV, so rather than take a sabbatical, I applied to the Iowa Writers Workshop intending to tell this story as fiction.”

Verghese attended the workshop, and soon after, his story was published in The New Yorker. When the editors learned of his background—a foreign-born physician and a small southern town dealing with HIV—they invited him to write an outline for a long nonfiction piece. As a result, he was drawn into writing two nonfiction books, My Own Country and The Tennis Partner.

Regarding his career as a fiction writer, Verghese shares, “I always wanted to write the kind of novel that would do what those other books did for me: bring a young person to medicine with a sense of the romantic, a passionate pursuit that will satisfy the reader.”

“There is a saying that character emerges when people make decisions under pressure. In medicine, I got to see that over and over again. It is very touching and tragic sometimes.”

If you haven’t read Cutting for Stone, treat yourself to a multisensory journey where Verghese’s words transform into scents, textures, and emotions that pull you into his epic tale. Pick up a copy of The Covenant of Water, another spectacular saga that early reviewers have raved about in Publisher’s Weekly, Kirkus, Booklist, and which received a great mention by Ari Shapiro in The New York Times.

Click here to learn more about Abraham and purchase his books.